Injuries from outdoor recreation like hunting, fishing, and hiking are usually less common than those of team or Olympic type sports. However, the very nature of what we do in the outdoors can lead to accidents that could quickly become dire if not treated quickly.

As with any emergency situation, your best tool is your brain. Make a plan, tell people where you will be, and trust your gut. If a situation looks to steep, wet, or choppy find another path. The framework here is simply a guideline and basic overview. Take time during the off-season to learn and practice these skills. Accidents and tragedies rarely happen, but you want to be prepared when they do.

The first step is to take a basic CPR and first aid class. With an aging demographic, both in our state and sportsmen in general, CPR can keep blood flowing to someone in cardiac arrest, which greatly increases the likelihood of survival. In adults and teens, chest compressions with a speed of 100 compressions per minute and a ratio of 30 compressions to two breaths is ideal. The Bee Gees’ song “Stayin’ Alive” is 103 beats per minute—singing that to yourself will help keep you at the right speed. As someone who has had to do this, you may hear ribs pop, but it’s worth it to keep someone alive.

For basic wound care such as burns, cuts, and nicks—whether from pocket knives, underbrush, or campfires—a basic first aid kit with small bandages and antiseptic will be sufficient. For bleeding, remember to control the pressure and elevation. The first is more important than the second. If you don’t have a first aid kit, a clean rag and duct tape can serve as a replacement.

For burns, use water or burn cream. Do not use butter or mustard or any condiment you have left over from lunch. Most of those will trap heat and potentially lead to more damage. In the case of a second degree burn that causes blistering, do not pop the blisters. Wrap the affected area in a dry dressing and pop a few Tylenol for the pain. Should the burn happen on a hand or foot, take extra care to keep the fingers or toes wrapped separately. This will reduce the rubbing and the resultant skin damage.

In the case of a larger laceration or a gunshot wound to the arms or legs, you will need more significant bandages and packing. A tourniquet can save a life when properly administered. They are not the cheapest item in your medical bag, but when it comes to bleeding there is no better way to stop a lower limb bleed than with a tourniquet.

In the case of a larger laceration or a gunshot wound to the arms or legs, you will need more significant bandages and packing. A tourniquet can save a life when properly administered. They are not the cheapest item in your medical bag, but when it comes to bleeding there is no better way to stop a lower limb bleed than with a tourniquet.

Take care with any major injury like this to record the time it happened. Tourniquets left on too long will starve the lower extremity of circulation and run the risk of killing the tissue. Most, if not all, will have a spot on them to write a time so that doctors can make the decision of when to remove the tourniquet or the limb.

Maybe it was a submerged log you didn’t see or a rock on the jetty that didn’t look as slick as it was, but falls and slips will happen. Most of the time a slip will result in wet clothes and a good laugh. Sometimes it can end with a sprain or break. Pain is subjective and without an x-ray, it’s hard to determine the true extent of an injury. Visual inspection is probably the best tool to determine a break. However, if the limb is shortened, deformed, not rotating correctly, or in the case of a compound fracture breaking the skin—you’ve got a broken bone.

Maybe it was a submerged log you didn’t see or a rock on the jetty that didn’t look as slick as it was, but falls and slips will happen. Most of the time a slip will result in wet clothes and a good laugh. Sometimes it can end with a sprain or break. Pain is subjective and without an x-ray, it’s hard to determine the true extent of an injury. Visual inspection is probably the best tool to determine a break. However, if the limb is shortened, deformed, not rotating correctly, or in the case of a compound fracture breaking the skin—you’ve got a broken bone.

If you suspect someone has injured their back or neck, DO NOT attempt to move them unless absolutely necessary. Moving a person with a neck injury could result in paralysis. Call or send for medical help and keep the person as flat and still as possible.

With a limb break, splinting the joint or bone won’t “heal” them, but will make moving them out of the woods more comfortable and reduce the risk of injuring nerves or blood vessels. Aluminum splints are lightweight and don’t take up much room, but if you haven’t brought that many medical supplies, any straight object like a fishing rod or stick can serve as a splint. Two splints—one for either side of the break—is a better tactic. Secure the splints using whatever is available: belts, tape, or even strips of clothing can work in a pinch. Remember, this isn’t a tourniquet. It should be enough pressure to keep the break from shifting, but not enough to cut off circulation.

With a limb break, splinting the joint or bone won’t “heal” them, but will make moving them out of the woods more comfortable and reduce the risk of injuring nerves or blood vessels. Aluminum splints are lightweight and don’t take up much room, but if you haven’t brought that many medical supplies, any straight object like a fishing rod or stick can serve as a splint. Two splints—one for either side of the break—is a better tactic. Secure the splints using whatever is available: belts, tape, or even strips of clothing can work in a pinch. Remember, this isn’t a tourniquet. It should be enough pressure to keep the break from shifting, but not enough to cut off circulation.

A common injury that is not often life threatening, but certainly cringe-worthy is being snagged by a fishhook. Since many hookings happen in the hand, you can decide whether to go to the clinic or remove it yourself. I personally hooked myself in the joint of the thumb and elected to have a doctor remove it instead, since my thumb is pretty valuable to me.

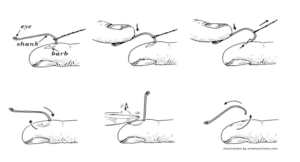

The two options for hook removal are the “string yank” and “advance and cut.” In cases where there is minimal barb or a treble hook, the string yank is preferable. Wrap the shank closest to the bend with strong line or twine, push down on the eye of the hook (giving the barb some room in the wound) and yank that sucker out as hard as you can. While this option sounds gruesome, you reduce the number of punctures and the potential for infection down.

The two options for hook removal are the “string yank” and “advance and cut.” In cases where there is minimal barb or a treble hook, the string yank is preferable. Wrap the shank closest to the bend with strong line or twine, push down on the eye of the hook (giving the barb some room in the wound) and yank that sucker out as hard as you can. While this option sounds gruesome, you reduce the number of punctures and the potential for infection down.

If the barbs are too aggressive, the hook is already running close to the skin (or in your ear or nose), or there is no clear way to yank it out, use the Advance and Cut method. You will need a set of pliers to cut the shank of the hook. As smoothly as possible “set” the hook so the barb  completely breaks the skin. Cut off the barb and withdraw the now smooth hook shank back through the wound channel.

completely breaks the skin. Cut off the barb and withdraw the now smooth hook shank back through the wound channel.

Between rusty hooks and fish slime, hook injuries can get infected quickly. Be sure you treat the wound with any available antiseptic and quickly see a doctor for antibiotics and possibly a tetanus shot.

This was a short list, but covers some the most universal of injuries and treatments. If everyone took a few hours for a first responder class, there could be a dramatic reduction in accidental deaths. This isn’t meant to scare you, but hopefully you and other outdoorsmen will behave safely and carry the items you’ll need to prevent tragedy. As always—stay safe and I’ll see you in the field.